In this series, teachers explain the means they are recreating historical methods, and how this impacts their investigate nowadays.

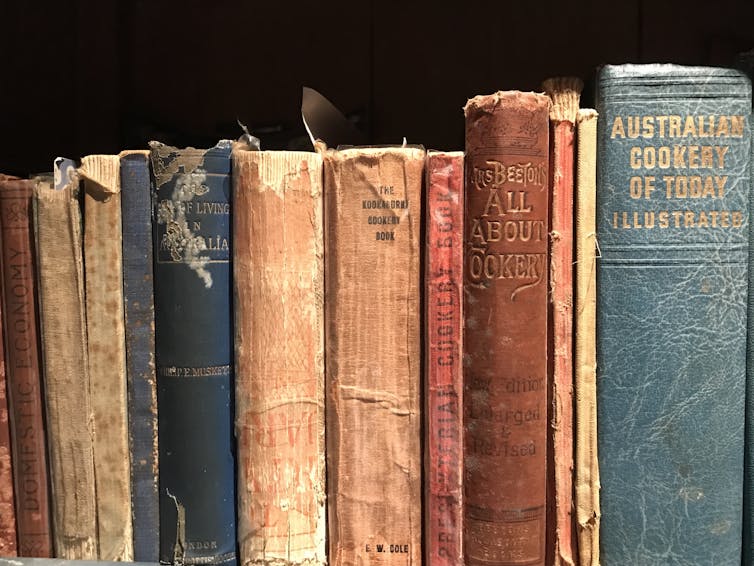

Previous recipes and cookery books are increasingly becoming recognised as archival information, documenting extra than just the food items that was eaten in the past. They support us keep track of consistencies and improvements in our tastes and traditions, and in the methods and systems we employ or depend on to put together a dish or meal.

Regardless of whether hand published or commercially created, the point that the recipes had been recorded signifies the author felt the resulting meals were being truly worth taking in.

When you flick by means of old Australian recipe publications, you will uncover some of the dishes are common, if not the exact same (“fricasees” and “ragouts” we now know as casseroles), when many others, these types of as flummery and blancmange are echoed in today’s much more innovative bavarois and pannecotta.

Other dishes which ended up after common in old cookbooks are curious or even peculiar to the modern prepare dinner, in particular people manufactured with meat cuts that some Australians may balk at: mock turtle soup (manufactured with a calf’s head), brawn (manufactured from a pigs’ head), calves’ toes jelly and boiled tongues currently being standouts.

As a historian with a Le Cordon Bleu Master’s diploma in gastronomy, (which I describe as the research of foodstuff and food items cultures), I am an intrigued by food items these as these. They are however well known in quite a few other cultures’ cuisines, but have dropped their place in Australia’s everyday culinary repertoire.

Why have they disappeared from our menus, and what does their absence from our kitchens, eating tables – and cookbooks – say about contemporary foodstuff selections?

Jacqui Newling, Writer furnished

Sensory and visceral

I get a quite fingers-on solution to looking into our meals heritage. My gastronomy diploma is an academic qualification – I am not a formally educated cook dinner, enable by itself chef. I have an Anglo-Celtic history that has not exposed me to the greater part of “lost” dishes mentioned earlier mentioned in the standard program of life.

In buy to have an understanding of them – and, importantly, the processes involved in making them – reading recipes is not plenty of. To write or talk about them with any authority, I require to encounter them myself.

I do not profess to be exactly recreating the previous or replicating the approaches and ensuing dishes. Technological and food stuff basic safety specifications have altered the substances and important devices to prepare dinner with them, but my experimental and explorative “forensic” exercise routines have been enlightening and instructive.

Jacqui Newling, Writer presented

They have supplied me with a far much more personal link with these dishes and appreciation of the time, expertise and effort and hard work required to make them – even with modern-day cooking facilities – than words on a website page could ever conjure.

The sensory and, at occasions, visceral mother nature of creating these dishes has been notably instructional, but normally challenging and discomforting.

I recognise now the obscure, nondescript but unique scent that is emitted when reconstituting jelly crystals as that which emanates from boiling calves’ toes: the fruity flavours and colouring a thin veil for the legitimate origins of animal-derived gelatine.

Just the considered of managing an ungainly, astonishingly massive, dense and heavy ox-tongue, trimming away the unsightly connecting ligaments and peeling its slim but leathery pores and skin from the organ would make me uncomfortably acutely aware of my personal tongue’s anatomy.

Cooking full animal heads – their eyes staring back again at me (accusingly? beseechingly?) as the pot bubbled away on the stove – was fairly disarming.

Jacqui Newling, Writer offered

Dismembering the pig’s deal with to retrieve the edible components for brawn (cheeks, jowls, palate, tongue and snout) is a sticky, slippery and messy work.

When these experiential and embodied forms of self-schooling have elicited inner thoughts of repugnance, to me they are tangible strategies of connecting the earlier and the existing, sharing experiences with cooks who also made these dishes or adopted these recipes.

Slippery, slimy and oozy

Psychological responses are of program unique, and imbued with cultural and particular indicating. My thoughts of distaste or revolt may not have been seasoned by cooks and diners who welcomed these dishes on to their tables.

With the gradual disappearance of local butchers’ stores doing work with complete animals, our meat, poultry and fish is generally bought in plastic packaging, generally deboned or filleted with skin removed, trimmed of fat and sinew, ready-portioned, perhaps marinated and completely ready to prepare dinner without the need of even further handling.

Humidity sachets and packaging that assist soak up fluids and odours make us less tolerant of the natural realities of animal pieces that are messy, bloody, sinewy, gristly, viscous, gelatinous, slippery, slimy and oozy.

Even though handy and time-conserving for customers, these preparations distance and disconnect buyers from the supply animal. We are losing realistic capabilities, but also the sensory connections and emotional sensibilities that come with performing with them.

Jacqui Newling, Writer offered

Numerous meat eaters who are comfy with common flesh-meats recoil at cuts that are reminders of the once-living animal, acquiring heads, tongues, ft and tails revolting, possibly horrifying, even barbaric.

Conversely, nose-to-tail dining, which tends to make use of just about every edible portion of an animal is lauded as a respectful and dependable acknowledgement of the environmental impacts of meat production and a way of honouring the life taken from an animal bred for consumption.

If we take into account the adage that food need to not just be good to consume but very good to feel about – morally and ethically – is resisting or rejecting these food items prejudice or a mark of refined style? Were being past generations crude and uncouth in their preferences and dining behaviors, or do they in point maintain the better ethical ground, coming confront-to-experience with the fact of their foods resources?

Jacqui Newling, Writer furnished

A recipe to attempt: mock turtle soup

Get a calf’s head as clean as probable, break up it and choose out the brains, wash and clean it perfectly and lay it to steep in chilly water for an hour. Then put into a stewpan with plenty of h2o to cover it, and two or a few pints more than established it on the hearth to boil, permit it simmer 1½ hours choose out the head, and when cold more than enough reduce [the meat] into parts, from 1 inch sq., and peel the tongue and reduce it into items, only smaller, and put these into a pan until the following working day, protected with a tiny of the liquor.

Then put all the bones of the head, and about 4 lbs of shin beef into the liquor in the stewpan. To this liquor when boiling, must be extra the rind of a lemon, 1 turnip, and a little mace and allspice, and a bunch of sweet herbs with white peppers and salt to taste. Enable these boil slowly and gradually for 5 hours and then strain.

Warm up the next day with the pieces of meat, egg balls and two or a few glasses of white wine (sherry favored).

— Mrs. Arthur Hardy’s recipe. The Kookaburra Cookery Ebook, The Girl Victoria Buxton Girls’ Club, Adelaide, South Australia. 1912.