Two weeks ago, when the current Israel-Palestine crisis began unfolding in the Gaza Strip, I noticed that a lot more people—especially non-activists—were talking about it in public. But in my part of the woods, the food world, the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories hasn’t really been a topic of conversation, though diners have long-embraced the region’s cuisines at Israeli restaurants like Philadelphia’s Zahav and Oren’s Hummus in San Francisco. If there was any conversation about Palestine, it was largely driven by Arab American women like chef-activists Amanny Ahmad and Reem Assil.

More commonly, we in food whisper about the issue similarly to how London chefs Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi bring it up in their popular cookbook, “Jerusalem”: While they allude to the ugliness of the long-running military occupation in their introduction, the text tends toward a laissez-faire attitude toward it. Conflicts over the ownership of land, culture and food are futile, they write, “because it doesn’t really matter,” and worrying about it would spoil the pleasurable act of eating. It’s a very political answer, seemingly designed to not piss anybody off. But then again, why are we asking restaurant folks to say anything about this?

“People listen to chefs,” said Preeti Mistry, a local chef and podcast host who is also known for speaking up about issues as broad as whiteness in fine dining culture and prejudice in food media. Recently, they began sounding the alarm on COVID’s brutal impact on India, using a fundraiser at Windsor restaurant PizzaLeah to raise money and awareness. “Whether you admit it or not,” Mistry said, “you’re a leader and people look to you.”

From left: Habibi Bar owners Andrew Paul Nelson, Essam Kardosh and Bahman Safari, Thursday, Sept. 24, 2020, in San Francisco, Calif. The pop-up is located at Bacchus Wine Bar.

Santiago Mejia / The ChronicleI asked the same question of Essam Kardosh, Bahman Safari and Andrew Paul Nelson, the founders of Habibi, a Russian Hill wine bar. On May 12, the team published an Instagram post that encouraged their followers to donate money for Palestinian refugee aid and learn more about “the human rights atrocities committed by the apartheid state of Israel.” At that point, Habibi was one of a tiny handful of local establishments that had said anything publicly about Palestine.

For Habibi’s founders, two of whom are of Middle Eastern descent, speaking out is a clear way to signal that their bar is about more than just selling wine: It’s about being a community space for people who usually feel excluded from the wine world.

Muddled political messaging is not an option for them, having experienced it firsthand. Kardosh said that during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, he and his colleagues saw how the businesses they worked for struggled with maintaining neutrality out of fear of alienating customers and generating backlash. It was an attitude that they pledged not to replicate at Habibi, a place where they would be the ones calling the shots. “We didn’t want to perpetuate that cycle of silence,” he said. And to that point, their May 12 Instagram point specifically included the sentiment that “silence is violence.”

Safari, a gay Iranian American who says he has often felt like an outsider at predominantly white queer-owned establishments in the Bay Area, emphasized that inclusivity should be more than just ambience: It also means “speaking up when there are injustices being enacted.”

According to Nelson, many non-Black-owned businesses felt pressured to make statements about racial injustice last year, sometimes by employees and customers alike. “That pressure was good for this country and was good for the world—to finally begin to have a conversation about racial injustice and police brutality.”

And if you think talking about the Black Lives Matter movement in mixed company is tough, bringing up Palestine is practically impossible. Palestinian Americans are prolific in the Bay Area food scene, but several have said that talking about these issues in public forums historically sparked massive amounts of backlash and harassment, including accusations of anti-Semitism. It’s hard for members of the Jewish diaspora to talk about too, as writer Marisa Kabas articulated in a recent piece for Rolling Stone. She wrote, “because the conflict has so often been boiled down to a binary—you either support Israel or you support its destruction—for many of us it felt like a betrayal to even consider the other side.” Yet Kabas has also observed more young American Jews being vocal about their opposition to the occupation.

So far, few Bay Area establishments have said anything at all, but not because the people behind them haven’t been thinking about this.

“I’ve been quiet because it’s so complicated,” said Mike Raskin of Oakland pop-up Edith’s Pie. Raskin, like Kabas, has struggled with how to talk about these issues among others of the Jewish diaspora. “Judaism and Zionism are not the same thing,” he wrote to me. “As a Jew for the liberation of Palestine it’s important to recognize that when people advocate for a Jewish ethno-state, it unavoidably implies ethnic cleansing. We cannot rest on the laurels of historic harms done to Jews to justify causing harms.” He’ll likely say something on his public social media channels about this, but he’s still mulling on it.

Even making a seemingly neutral statement about how both sides are suffering equally during this recent crisis—which has killed hundreds of Palestinians and 12 people in Israel and displaced 74,000 Gaza residents—could upset people, as Yotam Ottolenghi recently learned. Discussing the issue in-depth takes more of a commitment than simply posting a black square on Instagram.

Despite the political risks of declaring unequivocable support for a free Palestine, Nelson said, “it’s more worth it to us to let those people know that we love them, that we care about them, that we’re thinking about them.” According to Habibi’s founders, many customers and colleagues in the wine world reached out to thank them for saying something.

Reem Assil of Oakland speaks to the crowd during a protest against President Trump’s new travel ban in front of the Federal Building in San Francisco, CA, on Thursday March 16, 2017.

Michael Short/Special to The Chronicle 2017Perhaps one of the most important aspects of the Bay Area’s food scene is that the idea of hospitality folks taking activist turns isn’t so strange, with a legacy that includes the thrilling early days of California cuisine in the 1970s and the essential present-day work of Ohlone chefs who preserve their culture through food. There is plenty of space for political allyship here, and plenty of people willing to listen to what hospitality workers—community leaders, as Preeti Mistry called them—have to say.

On the podcast

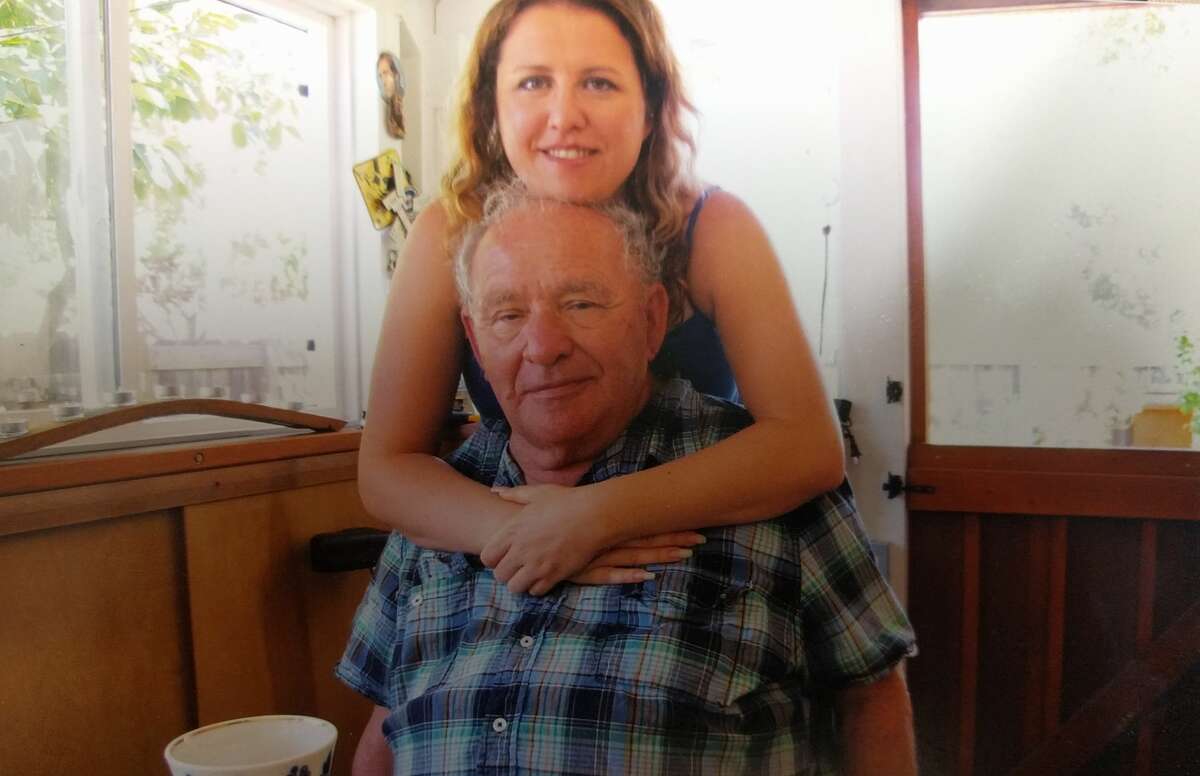

Susanna Zaraysky’s father, Isaac Zaraysky, 86, lives in a nursing home. Preparing meal kits for him been has been critical to feeling connected to him during the pandemic.

Courtesy Susanna Zaraysky

This week’s episode of Extra Spicy is all about the things we’ve cooked during the pandemic, with tender tales of feeding loved ones and culinary catastrophes alike. We catch up with writer Danny Lavery and Chronicle reporter Annie Vainshtein to ask them what they’ve learned about their eating habits, as well as their ovens. And we talk to San Jose author Susanna Zaraysky about the experience of cooking for her father who lives in a nursing home. Listen and subscribe here.

What I’m eating

Chicken Dog Bagels, a pop-up at Mission pizza spot PizzaHacker, makes the best bagels I’ve had in San Francisco. The sourdough everything bagel ($2.50) is chewy and robust, speckled generously with poppyseeds, toasted garlic and all the rest. Try it with the horseradish shallot cream cheese ($7) or as a sandwich.

At the Tailor’s Son, a new Northern Italian restaurant in Pacific Heights, I tried the phenomenal rotolo pasta ($21), a sort of roulade of fresh pasta wrapped around a filling of tender braised rabbit, spinach and fontina cheese. It’s nestled in a savory demiglace and rich bechamel sauce that you’ll absolutely be mopping up with bits of pasta. The roulade is gently broiled to finish, and the resulting caramelized cheese makes the dish reminiscent of a Tijuana quesotaco.

I bought an electric tabletop grill from H Mart, hoping to do a giant Korean barbecue grill-out once the weather stopped being such a bummer in San Francisco. So on one of the sunnier days last week, I gathered up lots of vegetables and meats from Chinatown markets and Korean grocery stores Queens and First Korean Market and set up a massive spread of bulgogi, spicy chicken, chile-marinated eggplants and seafood mushrooms and garlicky spot prawns on my balcony. For your information: First Korean Market sells those big, flavorful perilla leaves that are essential to making barbecue wraps.

Recommended reading

• In case you missed it, I wrote a little ditty on my return to eating inside of restaurants.

• Janelle Bitker and Esther Mobley delve into craft beer’s #MeToo moment, which sparked resignations, firings and promises for change at several Bay Area beer businesses. They include many accounts from craft beer professionals who earnestly want their industry to be better, and as I finished reading, I was left with a sense of hope.

• I’m really excited to watch “High on the Hog,” a new Netflix docuseries about Black American food, and this powerful essay about the series by Osayi Endolyn made me even more excited. As Endolyn writes, the show’s truth-telling about the history of American cuisine has been long overdue.

• Over at KQED, new food editor Luke Tsai has launched an ambitious project on Taiwanese food in the Bay Area. You might ask, “What Taiwanese food?” Tsai and his collaborators—a who’s who list of local Taiwanese American writers—will reveal where you can uncover the sprouts of the under-represented cuisine here.

Bite Curious is a weekly newsletter from The Chronicle’s restaurant critic, Soleil Ho, delivered to inboxes on Monday mornings. Follow along on Twitter: @Hooleil